Clark Wolf, Iowa State University Director of Bioethics

Proposals to regulate and limit the use of new technologies and medical procedures are regularly introduced in U.S. state legislatures, but no procedure in American political life is more controversial than abortion. At present, women in the United States have the constitutionally protected right to make their own decision about whether to end a pregrancy through abortion. States and the federal government are prohibited from passing regulations that would intervene in this constitutionally private decision, and states may not take steps to deny women opportunities to exercise this right. Recent polls show that a slight majority of American citizens support a “woman’s right to choose,” and evidence suggests that support for abortion rights has grown stronger in recent years. Among elected officials, however, support for abortion is a minority view. According to a 2014 poll by the National Abortion and Reproductive Rights Action League [NARAL], more than half of elected U.S. officials fully oppose legal abortion. Only 14% of Americans hold this position. In a democracy, how can our elected officials be so unrepresentative of popular opinion? There are several likely underlying explanations for this phenomenon. Perhaps the most salient is that pro-choice voters treat abortion rights as a medium-level priority (perhaps because they perceive this right as secure), while anti-abortion voters regard abortion to be an urgent, high-priority issue.

It is widely projected that this controversial right will once again find its way to the Supreme Court in the coming term. The case most likely to come before the Court is from Texas. In 2013, the Texas Legislature passed a bill known as H.B. 2, which included a number of provisions that were justified in legislative debate as necessary to protect women’s health. The most controversial feature of H.B. 2 is that it requires that abortion providers in the state of Texas must have admitting privileges at a clinic within 30 miles of the venue where abortion procedures are performed.

Is this a reasonable requirement? Defenders of H.B.2 urge that abortion is a potentially risky medical procedure, and that there are sometimes complications. Because of this, they hold that it is reasonable to require that physicians who perform this procedure should be able to quickly and efficiently transfer patients in need to a clinic where they can receive appropriate follow-up care.

Unfortunately, most physicians in Texas abortion clinics do not have and cannot obtain admitting privileges at local hospitals. The reason for this is that hospitals restrict admitting privileges to physicians who admit a minimum number of patients per year. Abortion providers do not typically admit many patients, because abortion is a very safe procedure for the women who receive them. Linda Greenhouse of the New York Times reports that the complication rate is very low. From 2009 through 2013 the national rate of complications associated with abortion procedures was 0.05 percent. A smaller portion of those cases would involve serious complications that would require that a patient be moved and admitted to a different clinic. Because of the admitting requirement, H.B.2 is expected to have the effect of closing three-fourths of all abortion providers in the state.

Why would Texas legislators pass a provision to regulate a safe procedure? The reason is clearly stated in H.B.2 itself. The bill is not about women’s health, it is a bill expressly designed to restrict Texas women’s access to abortion. The first three sections of the bill discuss the state’s interest in “protecting the lives of unborn children,” not the state’s interest in protecting women’s health. Arguing on behalf of H.B. 2, Texas governor Rick Perry noted “To be clear my goal, and the goal of many of those joining me here today, is to make abortion, at any stage, a thing of the past.” And on signing the bill, he congratulated its supporters, saying “For all of you who stood up and made a difference, no one will ever have to ask you ‘where were you when the babies’ lives were being saved.’”

Governor Perry, the authors and supporters of H.B.2, and many Americans regard abortion as a murderous procedure that takes an innocent life. Others regard abortion as a necessity, but a decision that is essentially private. Under current U.S. constitutional law, it is a right, State governments have a constitutional obligation not to interfere with women’s ability to make their own choice about whether to carry an early–term fetus to term.

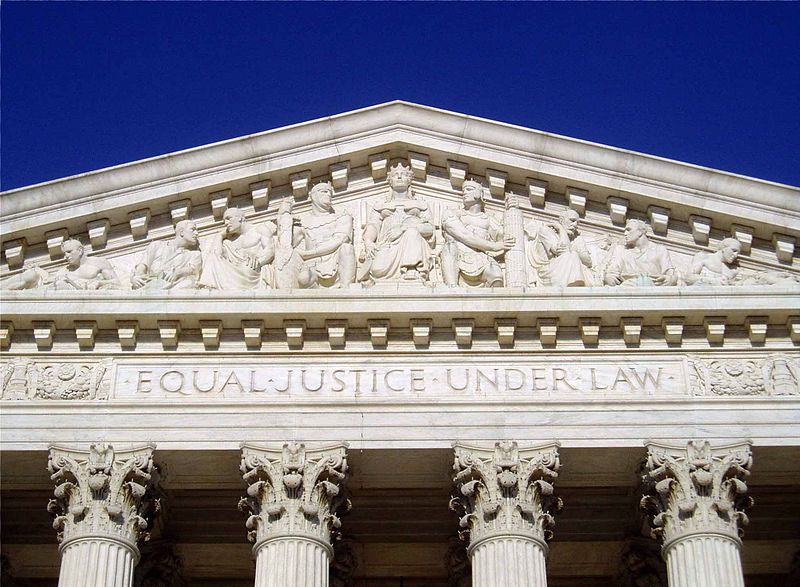

In the language of U.S. constitutional law, Texas’s H.B.2 places a burden on women’s constitutional rights. At what point does a state’s effort to create barriers to a woman’s constitutional right become an unconstitutional infringement? The case that governs this question in current U.S. law is a very long, controversial, and complex 1992 case known as Planned Parenthood v. Casey. In that case, the court ruled that it is permissible for states to put in place regulations that make it more difficult for women to obtain an abortion. The court wrote:

“As with any medical procedure, the State may enact regulations to further the health or safety of a woman seeking an abortion, but may not impose unnecessary health regulations that present a substantial obstacle to a woman seeking an abortion.”

The court went on to specify that “a State may not prohibit any woman from making the ultimate decision to terminate her pregnancy before viability.” And most importantly, the court articulated a test that prohibits states from placing an undue burden on a woman’s right. The court specified that an undue burden is “a state regulation that has the purpose or effect of placing a substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion of a nonviable fetus.”

Does Texas’s H.B.2 place a “substantial obstacle” in the path of women seeking abortions? Challenges to the Texas law have risen to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. Similar laws challenged in Arizona and Wisconsin have also risen to the Appeals court level. But judges on different appeals courts have adopted different interpretations of Casey’s undue burden test. According to [Judge Richard Posner](http://www.leagle.com/decision/In FCO 20131220161.xml/PLANNED PARENTHOOD OF WISCONSIN v. VAN HOLLEN) of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, the undue burden test requires courts to balance the burdens the restriction would oppose against the reasons that justify the restriction. In the Texas case, this would mean balancing the disadvantage imposed by H.B.2 on women seeking an abortion, against the potential gains to women’s health that might be expected from the additional protection that H.B.2 provides. If the gains to women’s health are negligible, as is suggested by the fact that abortion is a very safe procedure for women who pursue it, but the burden is significant, since women will find it difficult to get to an abortion clinic, then Posner’s interpretation would seem to imply that the Texas law must fail the test. Judge William Fletcher adopted standards very similar to the one Posner recommends when he reviewed and overturned Arizona’s restrictions on medication abortions, as did the Texas district court when H.B.2 was reviewed. “Plaintiffs have introduced uncontroverted evidence that the Arizona law substantially burdens women’s access to abortion services,” wrote Fletcher, “and Arizona has introduced no evidence that the law advances in any way its interest in women’s health.”

But Judge Jennifer Elrod, writing for the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, expressly rejected the “weighing” approach to the Casey undue burden test. According to Elrod, the courts in this case should defer to the legislature unless it can be shown that restrictive legislation lacks a rational basis. Under ‘rational basis’ review, the court has no business balancing the burdens imposed by the law against the law’s effectiveness in achieving its objectives. Elrod writes “In our circuit, we do not balance the wisdom or effectiveness of a law against the burdens the law imposes.” (also quoted by Greenhouse)

Such disagreement among the appeals courts is not uncommon, but makes it especially urgent for the Supreme Court to take a case that will settle the interpretive question. At the level of the Supreme Court, there are four justices (Scalia, Thomas, Roberts, and Alito) who may be expected to favor restrictions that limit access to abortion. Several of these justices have made it clear that they are ready to overturn the precedent that guaranteed a woman’s right to make this decision for herself. Four other justices (Kagan, Sotomayor, Ginsberg, and Bryer) may reasonably be expected to favor a woman’s right to abortion, and to be skeptical of statutes like Texas’s H.B.2 that restrict access. This leaves the crux of the decision, as so often in recent years, to Justice Kennedy. Kennedy voted with the court majority in Casey, which leads some commenters to predict that he will be skeptical of laws like H.B.2. But since Kennedy frequently votes with the conservative members of the court, it is difficult to predict what he might do in this case. The surprising fact remains that women’s ability to exercise a controversial right may ultimately come down to the views of a single person.